Cᴂdmon's Hymn and Modern Literary Criticism

The story of “Caedmon’s Hymn” moves and delights me. As told by the Venerable Bede (673-735), Caedmon was an illiterate and unmusical cowherd of Northumbria. Whenever village gatherings turned to music, Caedmon would excuse himself from the festivities to avoid being asked to sing. One such evening as the lyre was being passed around, Caedmon left the feast early and went directly to the cattle shed for his turn at guard duty for the night. After falling asleep, he had a dream that someone stood at his side and addressed him by name:

“Caedmon, sing me something.”

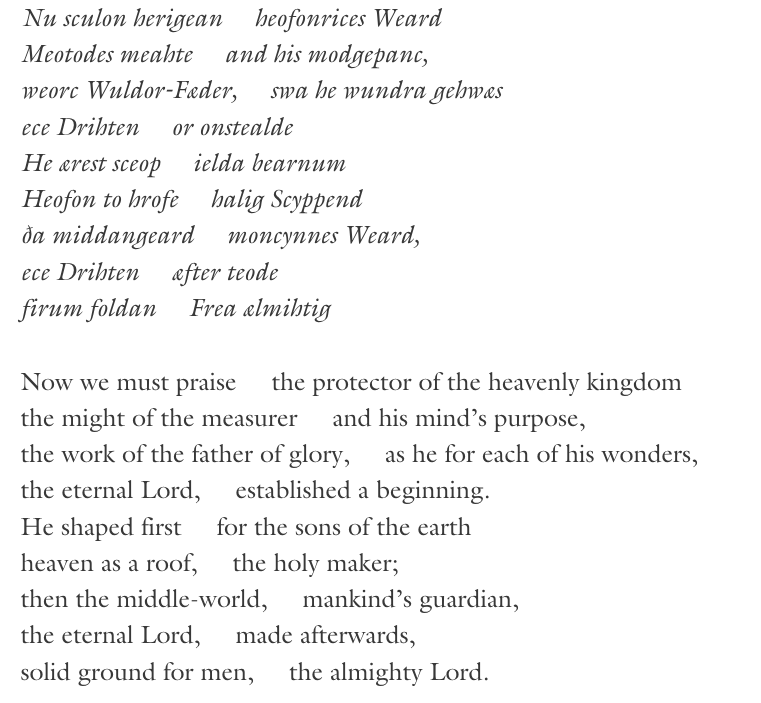

Embarrassed, Caedmon admitted his inability to sing. “All the same,” insisted the stranger, “you have to sing for me.” When Caedmon asked him what he should sing, the stranger replied, “Sing about the Creation.” Straight away, Caedmon began to chant the following verses:

After Caedmon awoke from this dream, he found he was still able to recall the song and recited it to the foreman of the local monastery where Hilda of Whitby (614-680) was abbess. As word of Caedmon’s gift spread, he was asked to recite the song before Abbess Hilda and an audience of learned men. The Venerable Bede relates that,

“It was evident to all of them that he had been granted the heavenly grace of God. Then they expounded some bit of sacred story or teaching to him, and instructed him to turn it into poetry if he could…And when he came back the next morning, he gave back what had been commissioned to him in the finest verse.”

Afterward, the abbess urged Caedmon to give up secular life and take monastic vows, which he did. Thus received into the monastery, he spent his remaining days learning the stories of sacred history and putting them to verse. By this work, Bede tells us, the former cowherd “sought to draw men away from the love of sin and to inspire them with delight in the practice of good works.”

Modern Criticism

Caedmon’s Hymn is believed to be the earliest extant poem of Old English. Notice its beautiful alliteration (e.g. herigean/ heofrinces, Meotodes/ meahte/ modgepanc) and use of caesura, the pause in the middle of each line which creates eighteen half-lines. Eight of these contain epithets describing attributes of God: Protector, Measurer, Glory-Father etc. The Norton Anthology of English Literature (Vol. A, Eighth Edition) notes that this formulaic style “provides a richness of texture and meaning difficult to convey in translation” (Greenblatt and Abrams, 24).

Sadly, I note that my Norton Anthology also imposes a critical attitude grounded in an Enlightenment bias of religious skepticism:

“Although Bede tells us that Caedmon had never learned the art of song, we may suspect that he concealed his skill from his fellow workmen and from the monks because he was ashamed of knowing, ‘vain and idle’ songs, the kind Bede says Caedmon never composed. Caedmon’s inspiration and the true miracle, then, was to apply the meter and language of such songs, presumably including pagan heroic verse, to Christian themes.”

In Anatomy of Criticism, Northrop Frye (1912-1991) tells us that “art [is] a communication from the past to the present.” He deplores literary criticism that seeks to reduce “cultural phenomena into our own terms without regard to their original character” (Frye, 24-25). Ours is a skeptical and disenchanted age, little given to mystical or religious experience. The materialist framework that automatically rejects the possibility that Caedmon’s lyrical gift had a supernatural origin is antithetical to the literary spirit that animated his and Bede’s age. The result is that modern scholars would sooner suggest that our humble cowherd was a duplicitous artist than entertain the possibility of miracles.

It’s attitudes like this that prompted writer and literary teacher William Gonch to advocate for a Christian critical tradition at Columbia University’s “Moral Imagination of the Novel” conference in 2019, where he observed,

“We don’t have a Christian criticism. We lack an ongoing interrogation into the distinctive aesthetic questions that arise when writers attempt to represent experience in the Christian tradition.”

It strikes me that if Caedmon the cowherd could embrace his calling to write sacred poetry that has been venerated through the ages, Christian writers today might make a conscious effort to revive a critical tradition that doesn’t shrink from questions of transcendence. For my part, I hope I’m able to do this in the reflections I write here.

Now for those who have eyes to see (and ears to hear), please enjoy this original setting of Caedmon’s Hymn performed by musician Peter Pringle.